This is the eulogy that I read at my grandmother's funeral yesterday.

Epitaph

In the days since my grandmother died, I've been meditating on a poem by C. S. Lewis, written after the death of his wife, and now carved on her gravestone in Oxford, England. C. S. Lewis writes,

Here the whole world (stars, water, air

Reflected in a single mind)

Like cast-off clothes was left behind

In ashes, yet with hope that she

Re-born from holy poverty,

In Lenten lands, hereafter may,

Resume them on her easter day.

Early in the morning of February 4th, Ruby Helen Lucille Smith left behind, like cast-off clothes, the mortal body she had carried with grace since 1917. The husband with whom she had shared a bed and a life for 72 years was with her, and held her hand, and felt the Holy Spirit fill the room even as her own spirit departed. Several hours later, as our family gathered around her deathbed to say one last good-bye, my mind was flooded with the memories of how that mortal body had served her over those years, and how she had used that body to serve others. So many meals: so many wounds bandaged, tears dried, cookies baked, diapers changed, grandchildren hugged, emails sent and demanded. How one quiet woman could represent so much activity and goodness is one of the mysteries of love.

We are gathered here today to celebrate the life, mourn the death, and rejoice in the homecoming of an extraordinary woman. Whether we knew her as friend, aunt, grandmother, mother or loving wife, I can think of no better way to honor her than to take a few moments to look through her eyes, to see the whole world as it was reflected in the single mind of Ruby Smith.

Her Friends

Deep and lasting friendships formed a constant background to my grandmother's world. Ruby Smith did not establish temporary relationships, or make friends out of convenience. The friends she made when she worked at Harry and David's in the 1940's, or when she attended Ashland Christian Center in the 1950's, or when she worked at the orthopedic clinic in the 60's and 70's, remained her friends for life. The number of these friendships necessarily diminished over the years, as she and Elmer remained healthy and vigorous, while more and more of their friends passed on. But as anyone who was a recipient of her emails can testify, her days, and Elmer's, were passed in frequent communication with old friends, visiting those who had grown sick, and helping those no longer able to fend for themselves. I do not believe that any friend of Ruby's could ever have complained of neglect or inattention; and a great many people in Ruby's world had cause to be thankful for her consistent hospitality and quiet kindness.

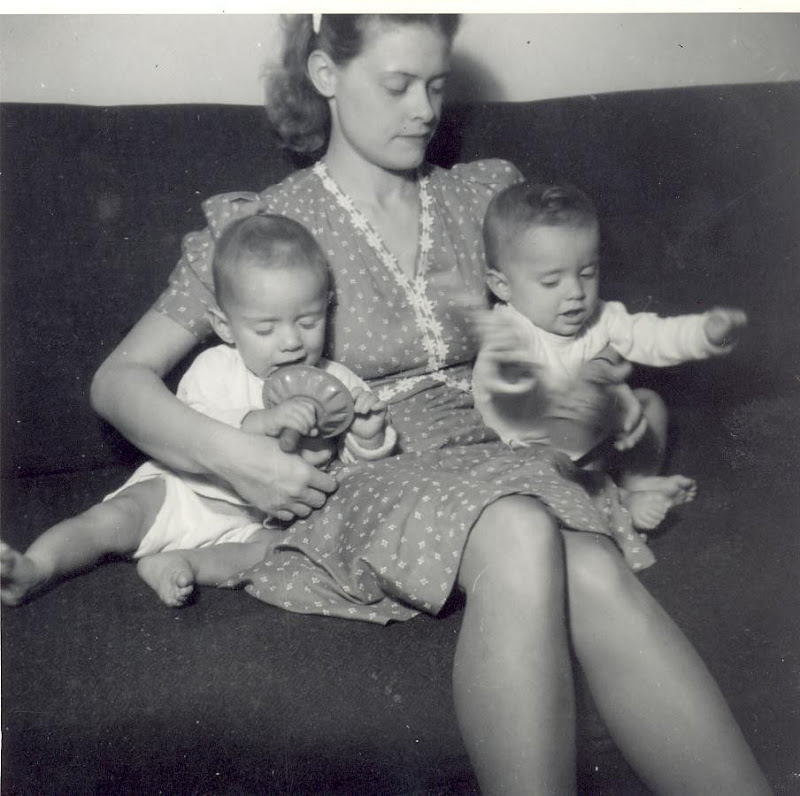

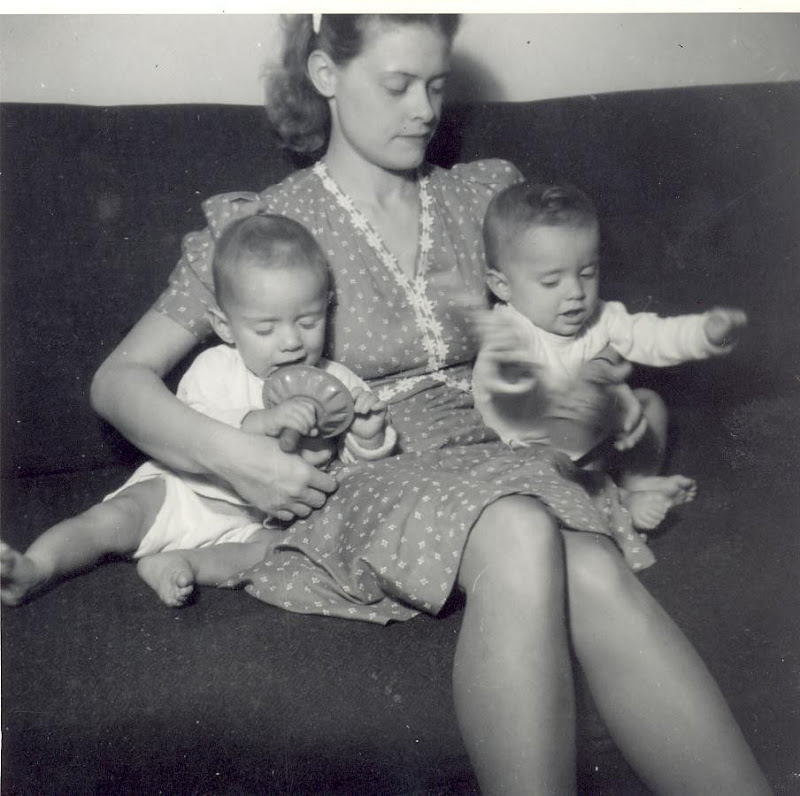

Her Twins

My grandmother's world revolved around her family. When my grandfather rushed her to the hospital on a warm July day in 1940, the two of them had little idea what was in store. The labor drugs knocked her out, and when she awoke, the nurse asked, "Did you know that you had twins?" Still groggy, Ruby responded, "I didn't know I had any."

Ruby assumed her new role as the mother of twin boys with gusto. For the next 18 years, she cooked, cleaned, mended, kissed, coddled, scolded, and chased her boys into adulthood. In 1957, my famously frugal grandparents splurged on a brand-new '57 Chevy for their two sons, and this was typical: they rarely bought anything for themselves, but nothing was too good for their boys.

Her Family

When Larry and Lloyd left home, married and had families of their own, Ruby found her world expanding once again. As the decades passed, through marriages, births, adoptions and virtual adoptions, she found herself the matriarch of a substantial and growing tribe. And again, although they rarely bought anything for themselves, they helped their grandchildren in any way that they could. Numerous house down payments, new cars, new computers, or college tuition payments had their origin in the bank account of a retired couple who never made more than $8 / hour.

Her Email

As the years passed, keeping the scattered and sundry members of her family connected became a substantial challenge. But many decades ago, she had instituted a tradition of regular letters to all and sundry, a tradition which she maintained until her 91st birthday. They started as hand-written letters, copied at the local post office, and sent out manually. About 15 years ago, we bought her an electric typewriter; her letters were perhaps longer after that, and of course typewritten, but otherwise unchanged.

It was probably 10 years ago that we pitched in and bought her first computer. She was horrified at the thought, and even called Larry in a panic: "They've bought me a computer, and they're bringing it over, and I need you to make them stop!" Nevertheless, we set it up for her, and walked her through turning it on. We showed her how to point and click with a mouse, showed her how to use a word processor, and how to access the Internet with a browser. She remained unimpressed.

Then we showed her email.

We had no idea we were about to create a monster. We should have known by the way her breath quickened when she saw us adding email addresses to the "To:" line. She watched us change fonts, and then email backgrounds, her eyes narrowing. She sat down. We showed her how easy it was to reply to her emails, and how easily she could reply to ours. The look on her face grew sharp, and hungry. She wanted this.

The monster was born.

Ten years, three computers, two printers, and many thousands of emails later, we learned that the monster must be fed. If Grandma didn't get twenty or thirty emails a day, she felt neglected. She forwarded emails like a fiend. She kept track of who had sent her emails recently and who hadn't. Woe betide the grandson who neglected to email his grandmother, for his neglect should be broadcast to the entire family, and then some.

As to the letters: they were just the daily life of a woman who had seen 90 summers in her lifetime, and 90 winters; who had watched three generations grow up in her house; who had cooked more meals than I know how to count and fed more hungry descendants than I care to; who watched the husband she loved dearly for 75 years grow old alongside her. It was just life; but it was life.

Her Husband

Ruby's world held nothing of greater worth than a skinny red-haired refugee from the Depression, fresh off the Salmon River, with an empty wallet and few prospects for filling it. Since their first walk home, and their first kiss under a Montana sky, Ruby had eyes for little else in this world. Most of you know that two weeks after she graduated from high school, Ruby and Elmer eloped – and that when they returned to Kalispell, they kept their marriage a secret for six months. It is the stuff of family legend that Ruby's father began to suspect something amiss only when Elmer began coming down from Ruby's bedroom for breakfast.

Ruby and her husband were inseparable. One story of many will suffice. Until this week, I believe that the last time my grandparents spent a night apart was twelve years ago, in 1996. I was moving up to Oregon from Southern California, and it seemed entirely natural to me to ask my blind 83-year old grandfather to come down and help me pack. We left Los Angeles late, after many delays, and my grandfather kept me company as I drove the moving van through the night. We arrived in Phoenix early the next morning, and were both exhausted as we drove up to their house, parked and climbed out. As the eldest grandchild, I had grown used to my grandmother rushing out of the house to hug me whenever I came to visit, so I wasn't surprised to see the door fly open and Ruby run down the driveway. But this time she ran right past me and practically leaped into her husband's waiting arms. Only after some minutes of fussing over him did she manage a quick hug for me; and then immediately returned to Elmer's arm, hardly to be shook off. An eldest grandchild was a poor substitute for the husband she had missed so badly.

These stories are typical of their relationship: they loved each other passionately, unreasonably, completely. The Great Depression, wars and rumors of wars, social revolutions and real ones, passed by in the outside world, leaving their love untouched. Children were born, then grandchildren, and great-grandchildren; even age itself began to take its toll, but the strength of their love was renewed like the eagle's.

Her Death

For the Christian, death will always have two faces. It is true – it is blessedly true – that we rejoice, because Ruby is now with her Lord; and so long as the Lord tarries, the beatific vision which Ruby is now experiencing can be achieved in no other way than by walking the lonely valley of death. But make no mistake: death is an enemy, and we fool ourselves if we think otherwise, or belittle its importance. If death is not important, neither is birth. Death rips us apart from the world which God made good, and in which God placed us.

And Ruby's death was in this respect no exception. My grandmother did not want to die. "I never expected this," I heard her say repeatedly during her final weeks. "This is so sudden." Until three weeks ago, she had not seen a doctor for six years, and had never so much as taken an antibiotic. Her perpetual good health made the sudden weakness that took her all the more alarming. She worried about her dumpy, her house, the sudden flood of guests. Ruby's world was full of friends, family, and a husband whom she loved dearly, and it was not a world that she wished to leave behind.

Even so, even as her weakness grew and her own death grew more imminent, my grandmother revealed a grace that we had always suspected, and a sense of humor that we had not. She kept us laughing through our tears as she retold old stories, and a few new ones. She harangued her eldest great-grandchild into getting his hair cut. She refused to put to rest the rumor that she had actually proposed to Elmer. She revealed the existence of a stash of coffee she had long kept secret from my grandfather.

When her husband was being stubborn about something, she turned to him, wagged her finger, and said, "In a few days, you'll be the boss, but for right now, it's still me!"

At one point, as her illness dragged on, and her family refused to budge from her bedside, she said, "I can just imagine the headline on my obituary: 'FINALLY'."

My grandmother's death came three weeks after her diagnosis, and it was a blessing; but after 91 years, it was too soon. She died as she lived: much loved, surrounded by family, and fussing just a little.

Her New World

The whole world, as reflected in the single mind of Ruby Helen Lucille Smith, was as clear as daybreak, as simple as a stream, profound as the stars. If you had looked through her eyes, you would have seen a world as broad as a lifetime of friendship, as narrow and focused as her family, and as plain as the ten acres of earth on which she and her husband built a lifetime together. This is the world that Ruby Smith has cast off; but she cast it off in hope, with the faith that one day, when the world is made new, she will clothe herself with it anew: when this corruptible shall have put on incorruption, and this mortal shall have put on immortality.

In that reborn world, we know that God will wipe every tear from our eyes. But that world is not this world, and in this world, our tears are appropriate. So let us grieve for our loss; but Lord, do not let us grieve as those who have no hope. "For the Lord himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God. And the dead in Christ shall rise first; and then, we who are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air; and so shall we ever be with the Lord. Therefore, comfort one another with these words."